The future of syndicated access

We could use distributed access to prevent surveillance practices from spreading into scholarly publishing further.

The first thing I think of when I hear the word 'syndicate' is a sort of cartel — not necessarily the most positive word.

How I use syndicated access is in terms of distributed access — multiple access points to the same content. This means that information is accessible at its origin and in many other places. It means that we can access the same piecese of information in a rich ecosystem of alternative platforms.

One key value proposition of Open Access was always that of reuse; syndicated access builds on that.

Yet when we want to read a paper published in a PLOS journal (for example), we still go to the PLOS website. Unnecessarily so because anyone could rehost the content — I could do so here on my blog without any legal liability.

In a world of syndicated access we would access the same content in multiple places. This could help undermine the data surveillance machines that are already built by some big publishers and prevents others from building them too.

Plenty of people are concerned with the tracking that takes place on publisher’s platforms (e.g., >1,300 people signed the Stop Tracking Science petition). This concern is justified, like when Robin Kok and Eiko Fried requested their data from Elsevier and got more than they expected. Or when a company publishing research also sold data analytics to US immigration services. These events help us understand research publishing houses are no more — they are also becoming data brokers.

We could use syndicated access to prevent surveillance capitalism practices from spreading into scholarly publishing even further. One key point of surveillance capitalism is that of locking people into a platform, in order to keep them there for observation, tracking. It is what Facebook did, it is why the great migration from Twitter to Mastodon is so interesting.

Syndicated access can reduce the lock-in for open access content.

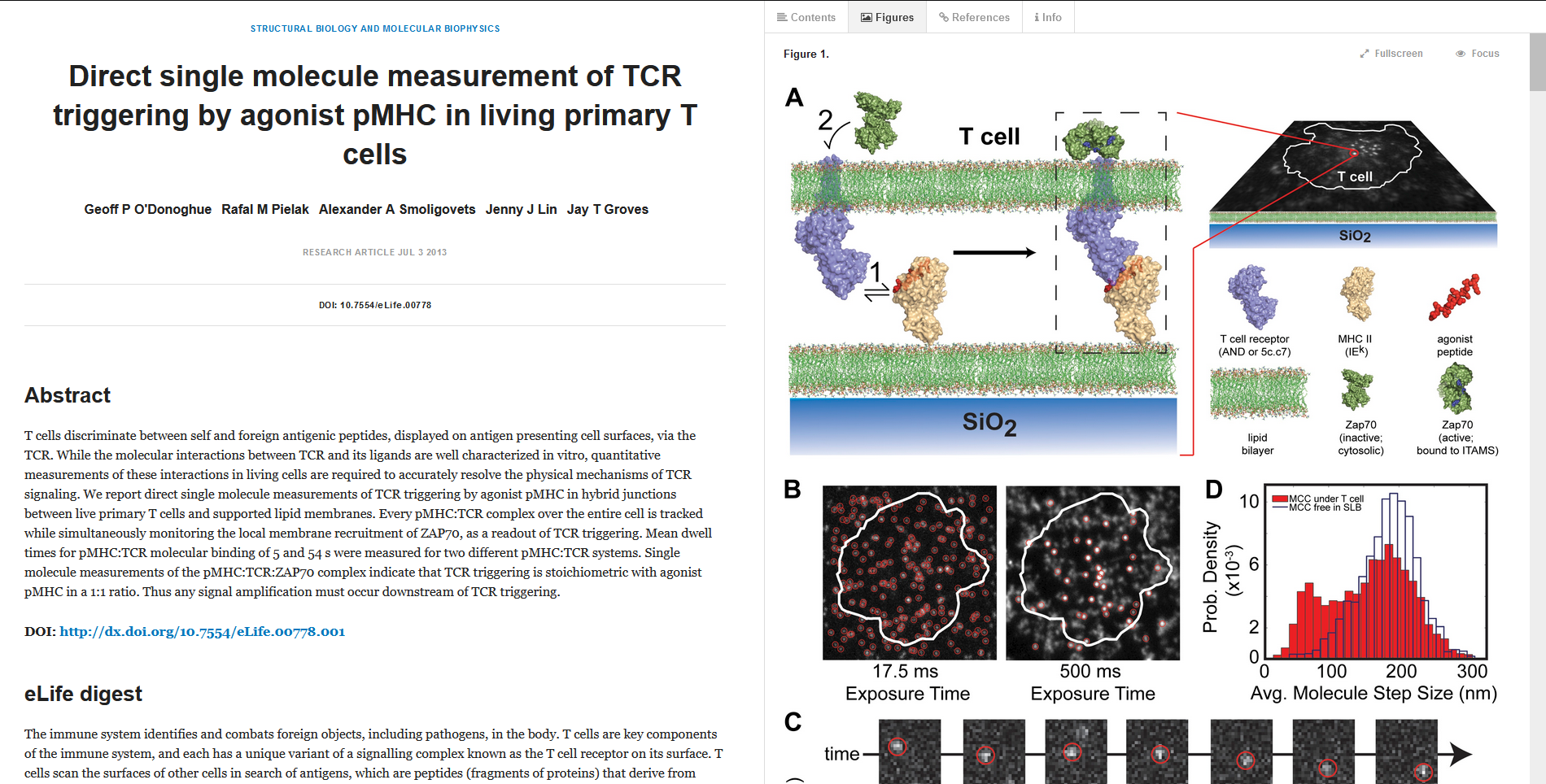

There have been some experiments to do this, but no attempt has scaled. We must work on increasing the number of access points to harness the full power of open access. One of my favorite examples of syndicating access is the (discontinued) ScienceFair app. It downloaded the raw XML that is used to create webpages for articles, and display it using eLife Lens. Here’s a side by side comparison of the regular paper and the Lens display.

We can already do it today for PLOS, Hindawi, and others that make their raw XML available for their open access papers. The availability of raw XML was always relevant for text- and data mining (TDM) - so you can guess who is and will not be making that available, even for open access papers.

Syndicated access is also on my mind as we progress ResearchEquals; there are a lot of questions as to what it means to create an access point. I will not start unpacking the how here, because I especially want to highlight that we could be doing more (why).

Cartel access

Beyond the reasons for syndicated access, my initial association of ‘syndicate’ and ‘cartel’ may not necessarily be too far off the mark after all. It also ties in to the Data Cartels in Sarah Lamdan's recent book.

When access to content is allowed to happen on different platforms because of contracts between parties who want you to go from one place to the next, we could call this “Cartel Access.” This could create the illusion of control about where to consume content, but keep you within a web of surveillance platforms.

One example is that of Thieme and ResearchGate, who created a “syndicate partnership” for papers. A spot-check of Thieme’s open access papers indicated I could not access the raw XML needed to create an access point. Thieme is promoting the use of ResearchGate by providing their papers to them and ResearchGate can be reasonably expected to provide something in return to make the partnership mutually beneficial (I would speculate that bit is data).

If we take this example one step further, we could see access points to papers pop up on verified platforms, bound by partnership contracts, which provide usage data in return to the original publishers. Raw XML provided in return for people's usage data, such that the data analytics strategy of the providing publisher can be strengthened. Verified platforms will be marketed as more reliable than unverified platforms, in an attempt to undermine access points that are not in a partnership with them. We have seen this play out with the “Version of Record,” used to undermine the veracity and integrity of the author’s version of the final paper (Green Open Access) to promote the pay-to-publish version of Gold Open Access.

Access points that do not join the cartel do not get verified and will not be able to provide as much content either.

Rejoinder

Cartel access does not exist as a thing today — I am speculating as an instigation for us to make syndicated access a reality. What would the next steps be? How would we discover this content? How might we prevent cartel access from becoming a thing? Those are questions we can start discovering together.

Comments ()