Gender gaps as symptoms of patriarchy

In this post, I share some thoughts on gender gaps in academia and society more broadly.

When we think of gender gaps in academia or society more broadly, we may think of very specific issues. But gender gaps are mere symptoms, with a common cause: The patriarchy. This is a system where maleness ultimately dominates, at the cost of everyone.

A concrete, quantified gender gap could be the wage differences between men and women. In Germany, where I live, it is 18%. In Romania, where you live, it is 4%.

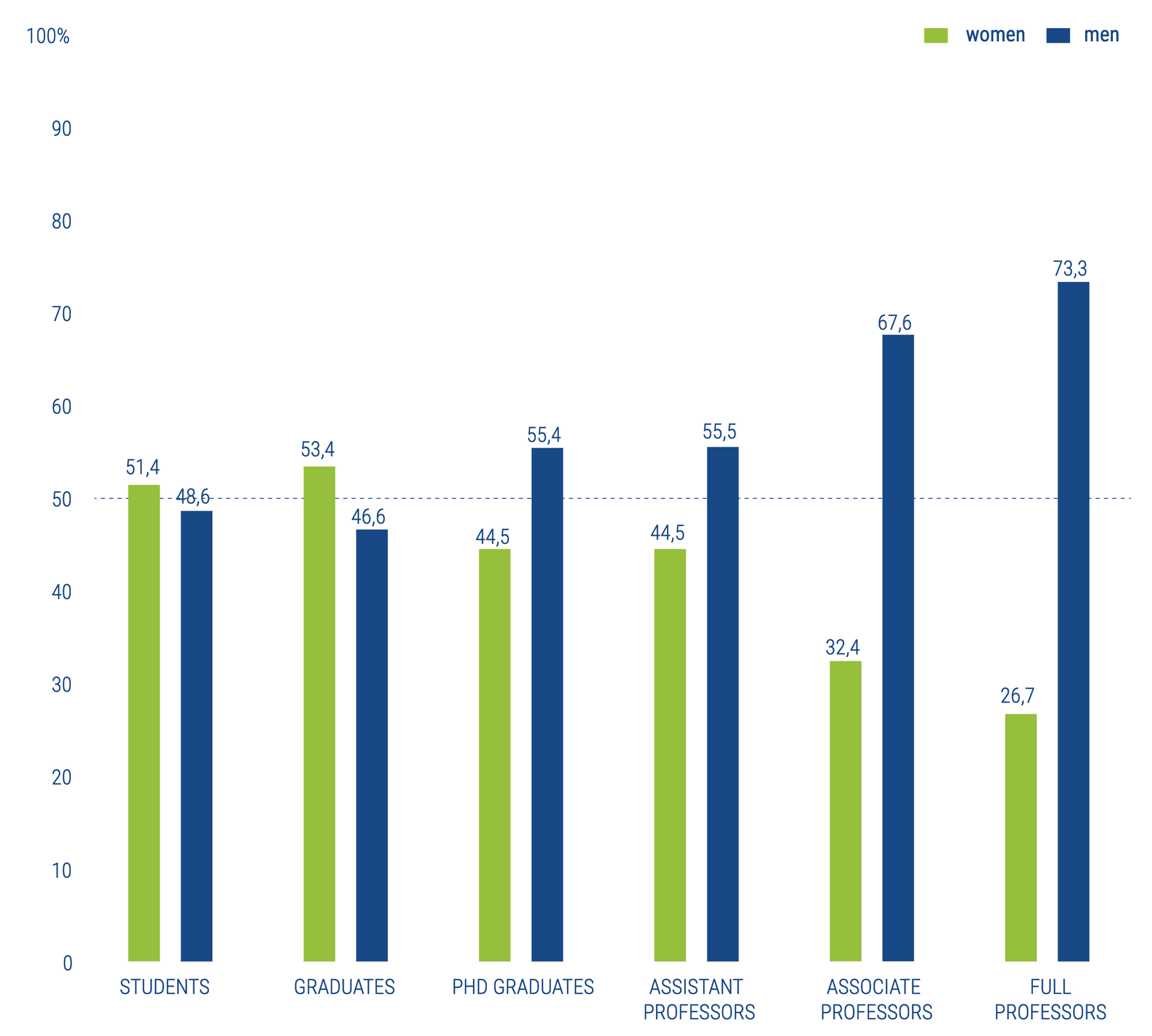

Another concrete gender gap, more specific to academia, is attrition of women throughout the career ladder. Despite the almost equal start for students, the gender gap widens over the course of a career. At the end of the career ladder, there’s three men for every one women professors. If we resolve this gap, it however does not mean maleness has been overcome - massculine traits may simply spill over into the women who make it to full professor (a type of queen bee behavior).

Another concrete quantified gender gap is the percentage of board members that aren’t men. The EU wants 40% of board members to be non-male by 2026, but will that mean they are less male in their behavior too? What is required of non-male folk to become a part of those boards? The gender gap goes deeper than the identity, it goes to behavior. We internalize power into how we act and what we believe is right - there is plenty of internalized sexism going around.

What I am trying to hint at here is that gender gaps tend to be helpful in quantifying differences, but when there are no more numeric differences, it does not mean there are no more qualitative differences. Are people able to be who they are in these spaces? Or are they conforming to the expectations of gender stereotypes?

This is where I’d like to introduce the concept of “Doing gender.”

In this concept, gender is nothing but a social performance. We construct our gender by how we behave. Sex assigned at birth only assigns the expectation of a role.

If we say somebody is being assertive, you may be more likely to imagine a man. If somebody’s caring for a person, you may be more likely to imagine a woman.

Likewise, in academia, the person speaking too much in a meeting is more likely to be a man. Establishing dominance and assertivity are masculine traits after all. The note taker and people organizer, making sure everyone is heard and tended to, is more likely to be a woman. Women are more likely to be unconsciously assigned this role.

This is the real, everyday and practical consequences of what it means to do gender.

To close gender gaps, we need to look beyond merely the numbers into what we do on an everyday basis. If we look only at the numbers, we will just start a game of whack-a-mole: Address one thing for another to pop up. How do we start undoing male dominance? More practically: What can you do to affect this?

Gender gaps indicate sexism, but misogyny is the policing of those gaps so that they stay or widen.

The philosopher Kate Manne, in her book Down Girl, explains misogyny as the act of punishing women who challenge male dominance — the patriarchy. Through that, we can see misogyny in practice easily.

Take for example, the history of #MeToo in academia, the time where many victims of sexual harassment finally felt capable to speak up about what happened to them.

Many male professors indicated that, as a result, they would no longer supervise or meet with women students one on one. They wanted to prevent sexual harassment allegations, ultimately against themselves. This is not a genuine concern about women’s well-being. If they were genuinely concerned, they would listen to women, instead of centring their own perspective.

Within Kate Manne’s framework, professors denying supervision to women is easy to be seen as misogyny - the punishing of individual women for women as a whole speaking up about sexual harassment. It reinforces the gender gap of speaking out against injustice.

And the lists of punishment go on and on: Speak up about sexism, and you are more likely to be seen as a trouble maker, and ultimately fired.

Just last week, professor Susanne Täuber was legally (!) fired from their Dutch University, for raising concerns regarding social safety, including around sexist behavior. The university said prof Täuber disrupted the employment relationship - and punished their behavior by firing them. Misogyny in practice, among many other things.

Misogyny ensures gender gaps stay. But when we talk about gender gaps as a whole, we often get stuck in a binary. Man. Woman. What about everyone else?

If gender is a social performance, if we do gender, then that means we are not restricted to two roles. We can generate new roles and new genders for ourselves. This is where discussion of many gender gaps break down, because it is not even being quantified.

Transgender folk, non-binary folk, they cannot even start to perform their role, to do their gender, because of the policing going on to maintain the binary. I experience it almost every day: Forms that do not have any other options than man or woman. The pressure to gender based on your name — the letters full of “Dear Sir” when I have never even disclosed to them I am a sir, madame, or anything else.

Academia has a big problem with gender beyond the binary. When people are redoing gender, they are simply erased, ignored, or punished.

Take for example the issue of research on gender.

Much research now exists to study and quantify gender differences, to help identify gender gaps, which is in a way, a good thing. In order to do that though, they have to determine the gender - something you cannot do without asking people, except if you resort to simply assigning it for them. If gender is a social role, assigning it is an act of male dominance in and of itself - taking the authority to assign it.

And this is exactly what many studies do: Assign gender.

Researchers use algorithms to pretend they can get an objective gender assignment, hiding behind statistics. My name is Chris, so I am likely to be a man because most other people named Chris identify as man. There is not even an option for that to be non-binary, trans, or anything else at this point.

The research then only identifies gender gaps between men and women, creating a much too simple model. What are the more complex gender gaps? Those that go beyond the binary and allow us to understand more deeply the interaction between identifying with the sex assigned at birth, also called cis gender, and being trans?

By assigning gender as a binary, the gender stays in a binary.

We do not even get to see the gender gaps that go beyond the binary - let alone truly start addressing how male dominance limits gender equality beyond the binary either.

All to say, gender gaps are real, yes.

Removing gender gaps in the numbers, however, does not remove the gender gaps in practice. We live in a male dominated society - from systems, to people, to the individual traits and behaviors. The secretary general of the United Nations said it will take another 300 years to reach gender equality at the current pace - but that’s only in the numbers. At this pace, it may take another 3000 years for it to go beyond the numbers, if we don’t start picking up the pace and struggling for it harder.

Comments ()